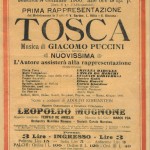

Some years ago someone shared on Facebook a poster of a “Madame Butterfly” production in a famous international venue. Music by Giacomo Puccini, libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, conducted by, directed by, blablabla.

No singers were mentioned.

Incredible.

I was so bewildered that I reacted to the post. “How can this be possible?” I asked. The author showed me then that – “at least!” – all artists were mentioned in the program given by the theater’s entrance.

“This cannot be a mistake of some unexperienced typesetter” I said to myself, “it’s a too big thing”.

I’m afraid I was right. Nowadays such posters without soloists’ names are more and more frequent, probably on their way to become majority.

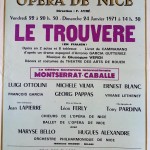

I have been a CD and DVD cover designer years ago, so I am aware that it’s not easy to create a nice layout with too many names going around. But back then all main soloists (usually from three to five) had to be mentioned. Big stars even required to have their own name written bigger than the others’. To me all this was normal because I never had a doubt about the fact that the most difficult task in an operatic performance is the one of singers interpreting main roles.

Do you doubt about it?

A conductor can get to the end of the show with the help of a good orchestra. A director can put together a show with the help of a good team. A soloist singing a big role is like a figure skater doing difficult jumps and choreographies, often on the edge, challenging extreme vocal difficulties during every performance. A soloist having a bad day might not get to the end of an aria and cannot be helped much: he/she is alone, “solo” to the very essence of this word.

The audience knows it or, at least, feels it: it’s very often to the soloists that the public gives the most intense reactions. When this does not happen it’s usually the conductor and/or the orchestra and chorus who win the game. In 25 years in this field I have witnessed only once a stage director getting more applauses than any one else in a show. It was well deserved I must say, but this says it all.

There might be many reasons why we got to this point. The era of big operatic stars like Callas or Pavarotti is well behind us and today there are too many singers around for too few jobs. A good singer is aware that he/she must behave because there’s a long queue of competitors waiting for the job just outside the stage door. We might lack stars today, but the average level got higher, to the point that a good soloist might be found in an opera chorus, not to speak of those houses which have their own soloists ensemble. This, in practical terms, means that singers have less power than before.

Today’s world is – in many ways – a visual world, and this certainly played a role in the rise of stage directors, costume designers and scenographers in the hierarchy of an operatic performance. Furthermore, slowly but surely, directors started being appointed as artistic directors or general managers in several opera houses around the world. Which is not bad in itself, of course!, but it may create a concentration of powers and a conflict of interests. Directors’ background is often non-vocal and non-musical, which also may create a short circuit in an art form which has vocality and music as its key aspects.

Is this enough to justify the absence of singers’ names on posters or web pages? The trademark of opera as a genre is the way it’s sung. Time is ripe to take note of it again.

Stefano Olcese